Paula de la Fuente Latorre, a sociologist specialising in gender and development. An expert in the Gender Mainstreaming Process with the EUROsociAL+ Programme and Ana Pérez Camporeale, a cooordinator in the Gender Equality area and head of the Help Desk for Gender Equality Policies with the EUROsociAL+ Programme

By Paula de la Fuente Latorre, a sociologist specialising in gender and development. An expert in the Gender Mainstreaming Process with the EUROsociAL+ Programme and Ana Pérez Camporeale, a cooordinator in the Gender Equality area and head of the Help Desk for Gender Equality Policies with the EUROsociAL+ Programme

The COVID-19 pandemic and the lockdown measures applied show a structural problem since they affect people in different ways: the data indicate that its consequences are increasing the gender gap. In 2021, the number of women and girls living in extreme poverty worldwide is expected to increase by 47 million, to 435 million.[1] In Latin America, by the end of 2020, the female unemployment rate will reach 15.2%, (an increase of almost 6% compared with 2019) and the poverty rate will rise to 37.4%, which means that 118 million Latin American women will be living in poverty[2]. The incompatibility of lockdown measures with paid work worsens the situation of women in terms of wages, unemployment and effective hours of work: 60% of women worldwide work in the informal economy[3] and they have had to close their businesses without access to welfare; at the same time, the lack of public services increases unpaid care and domestic work (UCDW), which favours the dynamics of “withdrawal from the labour market”. UCDW increased during the pandemic, while all other sectors showed sharp falls: internationally, the ILO calculates that the average contribution to GDP is 9.0%, with great disparities among countries[4] (in Argentina it is 16%[5], in Colombia it represents 22%[6] ). Women also play a leading role in the response to the crisis as domestic and health care workers (they represent 70% worldwide[7]), cleaning, in residences, etc. Domestic workers had to accept wage reductions, increased workloads, lay-offs without payment of benefits and even being detained in their employers’ homes during the lockdown[8]. Furthermore, violence against women increased as a result of the lockdown[9].

The pandemic coincides with the commemoration of 25 years since the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action (1995), which promotes the strategy of gender mainstreaming: “It is a strategy to make the experiences and needs/interests of men and women an integral dimension in the design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of policies and programmes in all political, social and economic spheres with the aim of having men and women benefit equally and eradicating inequality”[10]. The incorporation of this cross-cutting focus is reflected in the EU’s programme framework: The EU Gender Equality Strategy 2020-2025[11] and that of the Council of Europe 2018-2023[12], with a dual approach incorporating specific measures to achieve gender equality combined with the integration of the gender perspective. In bi-regional relations between LAC and the EU, the Santiago Declaration of 2013 (Point 38), contemplates the incorporation of the gender perspective, on the basis that “the inclusion of this perspective (…) will strengthen gender equality, democracy and promote fair and egalitarian societies”[13]. The 17 SDGs of the 2030 Agenda more or less explicitly define goals related to gender equality[14] (for example, Goal 16[15] refers to “access to justice for all” and proposes reducing physical, psychological and sexual violence, and putting an end to mistreatment, exploitation, trafficking and all forms of violence against girls and boys).

In the current context, the sustainability of the achievements in gender equality is at stake. The social role played by women, both in paid and unpaid work, has been shown to be essential, so they should also be the key players in the recovery measures. Failure in this area would contribute to perpetuating the “gender paradox of social cohesion” whereby women are the main providers of social cohesion yet they are systematically excluded from policies relating to citizenship rights and equal opportunities and participation. They assume the burden of care, providing a necessary “shield” for social protection, but they do not obtain any type of recognition, either in terms of contribution (income) or public investment (budgetary spending on gender equality policies)[16]. Mainstreaming the gender approach in EUROsociAL+ guarantees the promotion of public policies that affect gender equality in all spheres: from health and the economy, to social security and protection. It involves active treatment of gender equality so that the Programme’s actions equally benefit women, men, girls and boys. In practice, it involves applying a methodology for an approach that takes into account the different gender needs/interests throughout the cycle of actions, so that their effects in the context of advocacy can have a positive impact on social cohesion in the lives of women and men promoting equitable social models over the medium and long term.

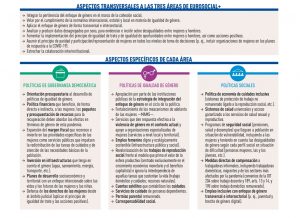

The challenges of mainstreaming gender in the EUROsociAL+ programme in the new post-COVID-19 scenario will consist of ensuring the actions offset the traditional inequalities, which in many areas of women’s lives have been exacerbated, so as to mitigate and halt the growth in the gender gap. From each of the lines of action, this would mean promoting measures such as:

GRAPHIC TABLE (JPEG)

Notes and bibliographical citations

[1]UN Women; UNDP (2020). From insight to action: gender equality in the wake of COVID-19. Recovered from: https://www.unwomen.org/-/media/headquarters/attachments/sections/library/publications/2020/gender-equality-in-the-wake-of-covid-19-en.pdf?la=en&vs= 5142

[2]ECLAC (2020). Care in Latin America and the Caribbean during COVID-19. Towards comprehensive systems to strengthen response and recovery. Recovered from: https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/45917/190820_en.pdf

[3]UN Women (9 April 2020). Put women and girls at the centre of COVID-19 Recovery: UN Secretary-General. Recovered from: https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/04/1061452

[4]ILO. Care work and care jobs for the future of decent work, p.4. Recovered from: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—dcomm/—publ/documents/publication/wcms_633135.pdf

[5]Argentine Ministry of Economy (2020). Care, a strategic economic sector. Measurement of the contribution of unpaid care and domestic work to gdp. Recovered from: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/sites/default/files/los_cuidados_-_un_sector_economico_estrategico_0.pdf

[6]UN Women Colombia; DANE Colombia (May 2020). Unpaid care in Colombia: gender gaps. Recovered from: https://www.dane.gov.co/files/investigaciones/genero/publicaciones/Boletin-estadistico-ONU-cuidado-noremunerado-mujeres-DANE-mayo-2020.pdf

[7]Boniol, M. et al. (2019). Gender equity in the health workforce. [Geneva]: Word Health Organisation. Recovered from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/311314/WHO-HIS-HWF-Gender-WP1-2019.1-eng.pdf?ua=1

[8]UN Women; ILO; ECLAC (2020). Paid domestic workers in Latin America and the Caribbean in the face of the COVID-19 crisis. Recovered from: https://www2.unwomen.org/-/media/field%20office%20americas/documentos/publicaciones/2020/05/06/estrabajadoras%20remuneradas%20del%20hogar%20v110620%20comprimido.pdf?la=es&vs=123

[9]UN Women. Policy Brief No. 17 (2020). COVID-19 and violence against women and girls: addressing the shadow pandemic. Recovered from: https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2020/06/policy-brief-covid-19-and-violence-against-women-and-girls-addressing-the-shadow-pandemic

[10]AECID guide for mainstreaming the gender approach. Madrid: AECID, 2015, p. 17. Recovered from: https://www.aecid.es/Centro-Documentacion/Documentos/Publicaciones%20AECID/Gu%C3%ADa_G%C3%A9nero_ENG.pdf

[11] European Commission. Strategy for Gender Equality 2020-2025. Recovered from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/ES/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0152&from=EN

[12]Council of Europe. Gender Equality Strategy 2018-2023. Recovered from: https://rm.coe.int/prems-093618-gbr-gender-equality-strategy-2023-web-a5/16808b47e1

[13]Santiago Declaration 2013. Recovered from: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/cmsdata/124264/ST_5747_2013_INIT_EN.pdf

[14]ECLAC. Gender autonomy and equality in the Sustainable Development Agenda. Santiago: United Nations, p. 32

[15]Peace, justice and strong institutions

[16]López, Irene (coord.). Gender and Social Cohesion Policies. Madrid: International and Ibero-American Foundation for Administration and Public Policies (FIIAPP), 2007, pp. 20-24