Climate change has put three out of every ten households in Central America and the Caribbean at risk. Added to this environmental vulnerability, social vulnerability has exacerbated by the effects of the pandemic, which is why it is a matter of urgency to implement comprehensive policies to reduce inequalities and alleviate poverty.

COVID-19 does not affect all people equally. Neither does not affect all territories to the same extent. According to UN-Habitat estimates, almost 60% of the population in Central America lives in urban areas, many of them built without town planning regulations. Sprawling, overcrowded neighbourhoods poorly connected and with few infrastructures and services, whose populations have been made more vulnerable by the pandemic. Informal settlements have been particularly hard hit due to the inaccessibility of drinking water for proper sanitation, overcrowding in homes and the difficulty of accessing health services. In addition, the pandemic has had significant negative effects on household economics, since many people who live in settlements, particularly women, are not formally employed. According to the International Labour Organization, 126 million women work informally in Latin America and the Caribbean. This represents almost 50% of the region’s female population.

“Since the pandemic began, the situation in our neighbourhood has been chaotic because we live in cramped conditions with up to 15 people living in tiny houses. There were three of us living our three-room house, but now there are eight, because my daughter and grandchildren have joined us. I I live on a government disability pension, but it is very small”, explains Alicia Bremes from Pueblo Nuevo, a neighbourhood in the Pavas district of San José, Costa Rica. In August 2020, the districts of Pavas and Uruca together made up more than 15% of the entire country’s active COVID cases.

“How can we wash our hands if we don’t have access to water? And how can we going to disinfect ourselves if gel is too expensive?” laments Bremes, who has suffered the consequences of the pandemic at home. “One of my sons fixes mobile phones and he has been out of work for months. I have another son with a disability who went to a psychiatric workshop every day and he has had a very bad time with nowhere to go. Because he is always out of the house, he caught COVID and had fevers and asphyxia, but he recovered. But a lot of my neighbours of all ages have passed away”, she says.

As Alicia explains, the neighbourhoods are in an extremely vulnerable situation. “Many mothers in the neighbourhood had been working as domestic cleaners in homes but they were let go because of the pandemic. COVID has also shut down much of the street vending that many families depend on for their daily meals. And psychologically, young people have suffered from loneliness and tension in the homes they have to share with a lot of adults”, she says. Therefore, it is essential to focus on the needs of the most vulnerable groups and try to cushion the effects of the pandemic that has quickly become a socio-economic crisis as well as a health one.

In this context, the Council for Social Integration (CIS) asked the Secretariat for Central American Social Integration (SISCA), with support from the European Union EUROsociAL+ Programme, and in alliance with United Nations agencies and programmes including the FAO, ILO and UN HABITAT, to prepare a Recovery, Social Reconstruction and Resilience Plan for Central America and the Dominican Republic. As Cristina Fernández, an expert in the EUROsociAL+ Governance area who has coordinated this work, explains, the Plan is a common regional roadmap and is made up of a series of strategic projects articulated around three areas for intervention: social protection, employment and sustainable urban development.

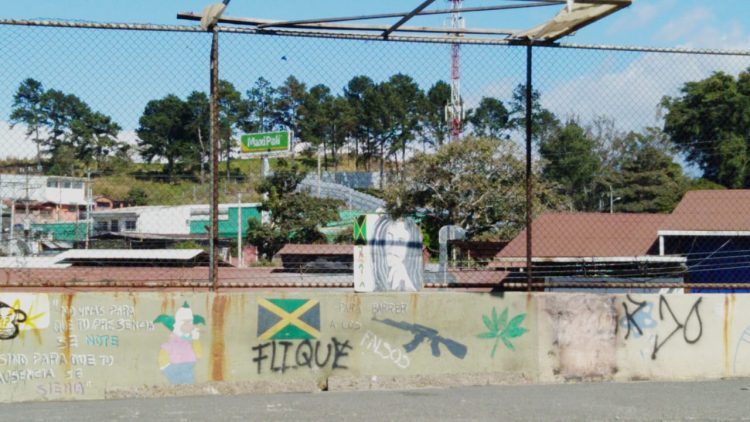

The Plan is focused on reducing poverty and socio-spatial inequality, the most obvious territorial manifestation of which is informal settlements, which account for an estimated 29% of the Central American urban population. “Despite national efforts to reduce the population living in informal settlements over the last 15 years, they are still extremely common. To which must be added the risks derived from climate change, which exposes a growing number of inhabitants to the effects of extreme weather events such as hurricanes or landslides”, the expert emphasises.

According to Fernández, “there is a pressing need to take a wider view and consider neighbourhoods as places that allow people to live in a city. Therefore, we need to provide housing and ensure that they have infrastructures, services and equipment, and that they are are connected to the remainder of the city and its opportunities”º.

It is a pressing challenge for a population for which every day counts and whose hopes are dwindling. “I don’t see a future because most of us are living in poverty and we don’t see a way out. But I keep on working as a community leader to be able to help, especially young people, on whom we have placed our hopes and who are being captured by drug trafficking networks”, emphasises Alicia Bremes.

For this reason, as Fernández points out, it is urgent to leverage additional financial resources to implement the Recovery, Social Reconstruction and Resilience Plan, “an instrument that will mitigate the effects of the pandemic and configure more resilient, socially just, egalitarian, and environmentally more sustainable societies”.